III. Texts used in Palabras

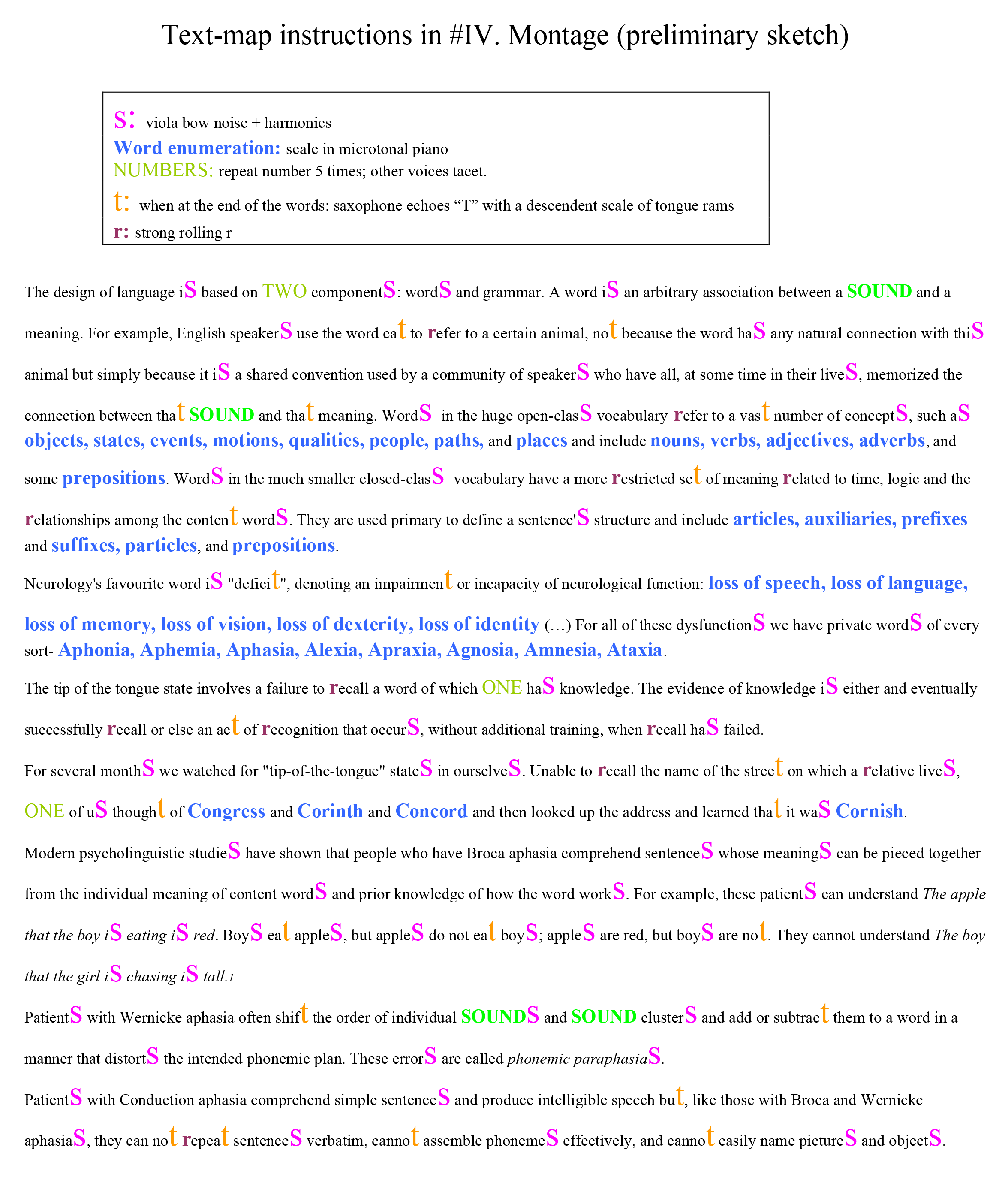

The design of language is based on two components: words and grammar. A word is an arbitrary association between a sound and a meaning. For example, English speakers use the word cat to refer to a certain animal, not because the word has any natural connection with this animal but simply because it is a shared convention used by a community of speakers who have all, at some time in their lives, memorized the connection between that sound and that meaning. Words in the huge open-class vocabulary refer to a vast number of concepts, such as objects, states, events, motions, qualities, people, paths, and places and include nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and some prepositions. Words in the much smaller closed-class vocabulary have a more restricted set of meaning related to time, logic and the relationships among the content words. They are used primary to define a sentence’s structure and include articles, auxiliaries, prefixes and suffixes, particles, and prepositions[1].

Neurology’s favourite word is “deficit”, denoting an impairment or incapacity of neurological function: loss of speech, loss of language, loss of memory, loss of vision, loss of dexterity, loss of identity (…) For all of these dysfunctions we have private words of every sort- Aphonia, Aphemia, Aphasia, Alexia, Apraxia, Agnosia, Amnesia, Ataxia-[2]

The tip of the tongue state involves a failure to recall a word of which one has knowledge. The evidence of knowledge is either and eventually successfully recall or else an act of recognition that occurs, without additional training, when recall has failed.

For several months we watched for “tip-of-the-tongue” states in ourselves. Unable to recall the name of the street on which a relative lives, one of us thought of Congress and Corinth and Concord and then looked up the address and learned that it was Cornish[3].

Modern psycholinguist studies have shown that people who have Broca aphasia comprehend sentences whose meanings can be pieced together from the individual meaning of content words and prior knowledge of how the word works. For example, these patients can understand The apple that the boy is eating is red. Boys eat apples, but apples do not eat boys; apples are red, but boys are not. They cannot understand The boy that the girl is chasing is tall.[4]

Patients with Wernicke aphasia often shift the order of individual sounds and sound clusters and add or subtract them to a word in a manner that distorts the intended phonemic plan. These errors are called phonemic paraphasias.[5]

Patients with Conduction aphasia comprehend simple sentences and produce intelligible speech but, like those with Broca and Wernicke aphasias, they can not repeat sentences verbatim, cannot assemble phonemes effectively, and cannot easily name pictures and objects.[6]

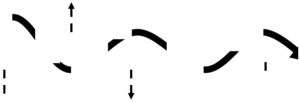

Saxo:

Dr P. was a musician of distinction, well-know for many years as a singer, and then, at the local School of Music, as a teacher. It was here, in relation to his students, that certain strange problems were first observed. Sometimes a student would present himself, and Dr P. would not recognize him; or, specifically, would not recognize his face. The moment the student spoke, he would be recognized by his voice.[7]

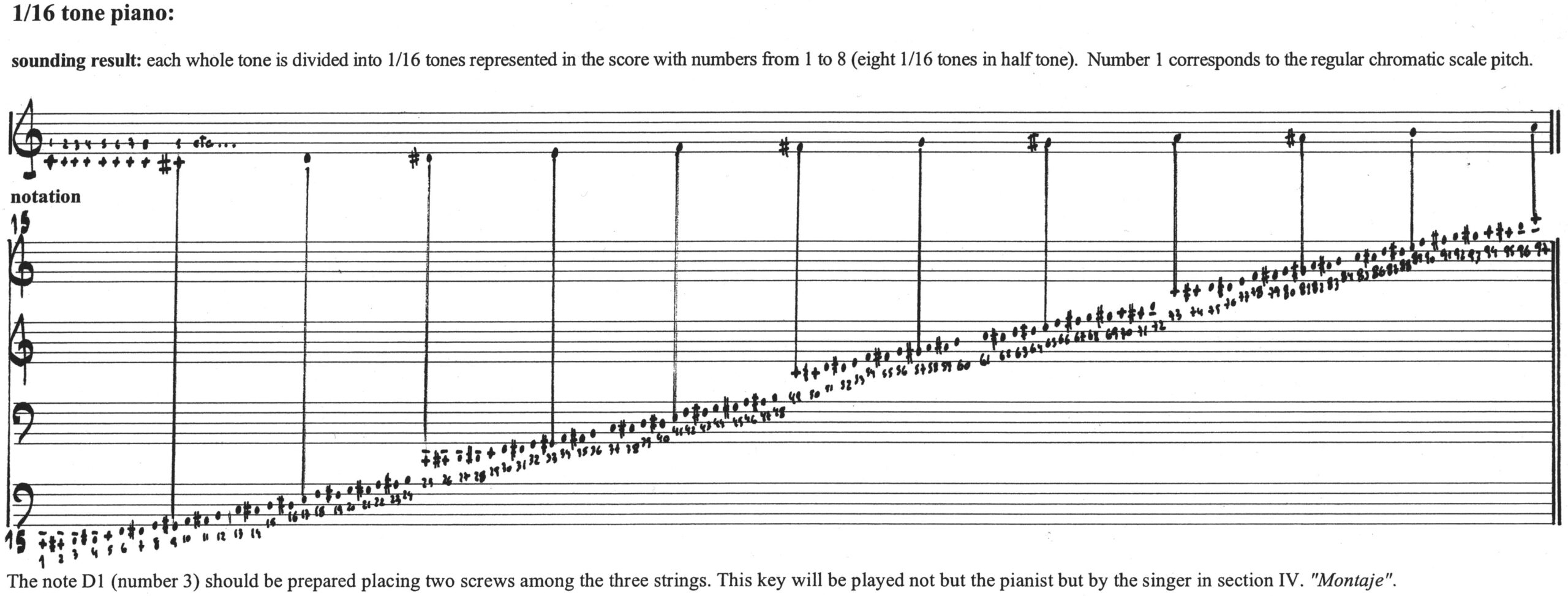

Piano:

But if he is interrupted and loses the thread, he comes to a complete stop, doesn’t know his clothes-or his own body. He sings all the time-eating songs, dressing songs, bathing songs, everything. He can’t do anything unless he makes it a song.[8]

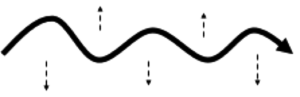

Viola:

I think that music, for him, had taken the place of image. He had no body-image, he had body-music: this is why he could move and act as fluently as he did, but came to a total confuded stop if the “inner music” stopped.[9]

[1]Kandel, E. Schwartz, J and Jessell, T. “Principles of neural science”; Mc Graw-Hill Companies, 2000.

[2] Sacks, O. “The man who mistook his wife for a hat”; Duckworth, 1985

[3] Norman, D. “Memory and Attention”; John Wiley & Sons, inc, 1969.

[4] Kandel, E. Schwartz, J and Jessell, T. op.cit.

[5] Kandel, E. Schwartz, J and Jessell, T. op.cit.

[6] Kandel, E. Schwartz, J and Jessell, T. op.cit.

[7] Sacks, O. op.cit.

[8] Sacks, O. op.cit.

[9] Sacks, O. op.cit.