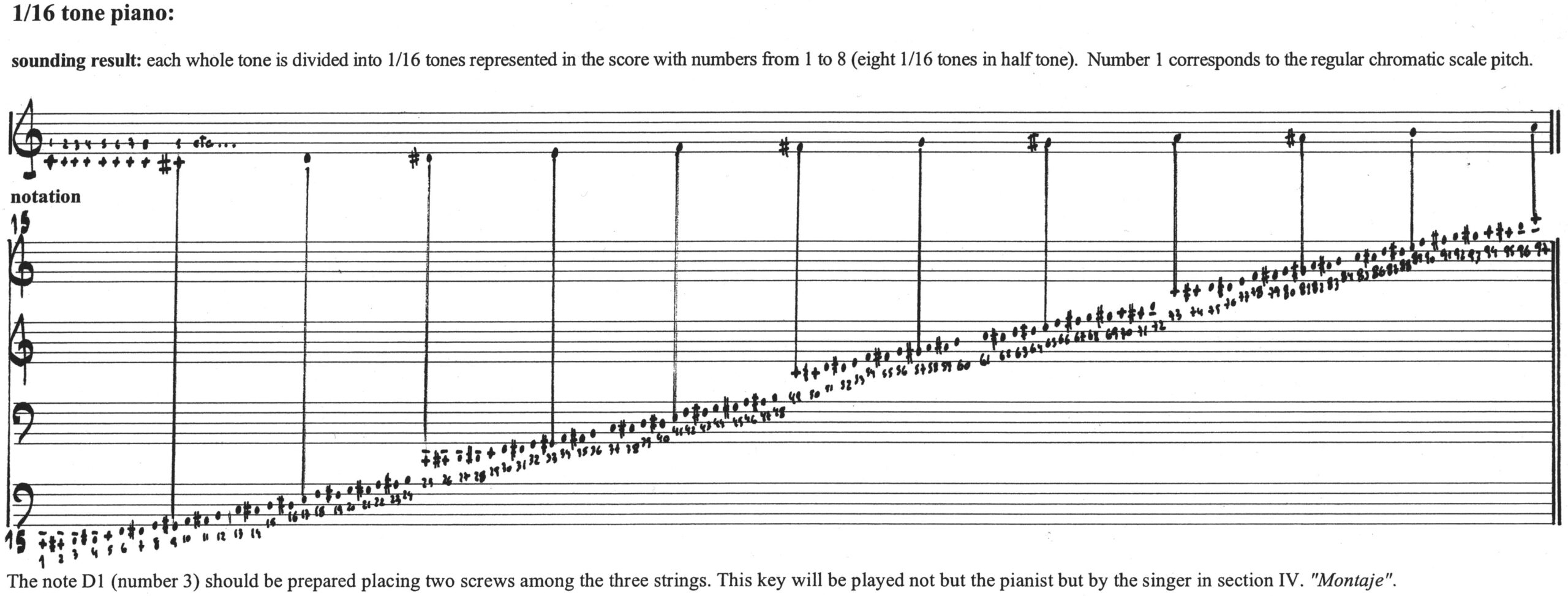

El libro de los gestos notas de ejecución en ocasion de su estreno el 2 de Agosto de 2007 por el ensamble Musas en Las Jornadas de Música Contemporánea en la Universidad de Santa Fe, dirigida por Hernan Diego Vazquez.

Estructura rítmica- una estructura vacía

La pieza esta construida en base a la idea de isorritmos. Estas estructuras rítmicas base se repiten constantemente en el discurso de la pieza, a nivel macro (forma de la pieza) y a nivel micro (fraseo).

Los isorritmos en si mismos no representan nada, ya que en la pieza aparecen con distintos “contenidos”: distinta instrumentación, tempos, armonías, alturas.

No es interesante el concepto del isorritmo en la pieza a nivel expresivo, ya que la misma estructura rítmica con un diferente contexto instrumental y musical significa algo totalmente distinto en cada nivel. Es un secreto del compositor que no es interesante difundir, pero si el análisis de estos isorritmos, pueden ser una herramienta para el estudio y el armado de la pieza.

Macro isorritmos

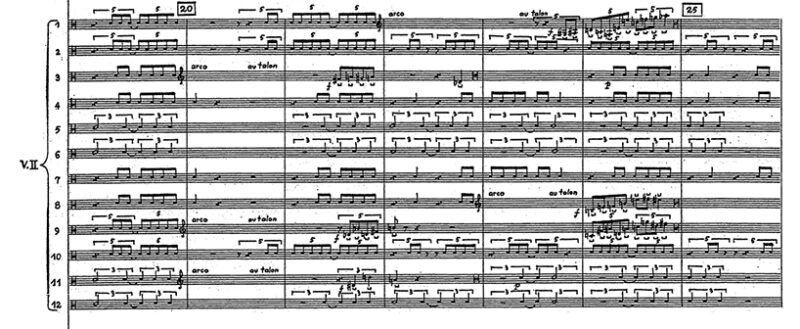

La pieza tiene tres secciones, cada una de tres paginas.

Sección 1: pagina 1, 2 y 3

Sección 2: pagina 4, 5 y 6

Sección 3: pagina 7, 8 y 9

En la primera pagina de cada sección se repiten los primeros 9 compases, con una pequeña variación.

Los 9 primeros compases de cada sección son exactamente iguales a los 9 compases siguientes. Generalmente uno de los instrumentos repite su línea textualmente y los otros instrumentos están filtrados[1]. Por lo que una sugerencia es tocar la repetición completa (ej.: 10 a 18) y luego repetirla con algunas zonas borradas.

Sección 1: Línea del cello se repite textual (1-9 igual a 10-18). Los otros instrumentos se repiten filtrados.

Sección 2 – línea del violín se repite textual (50-58 igual a 59-66), los otros instrumentos ídem.

Sección 3 línea de percusión se repite textual (igual a 99-107 igual a 108-115), los otros instrumentos ídem.

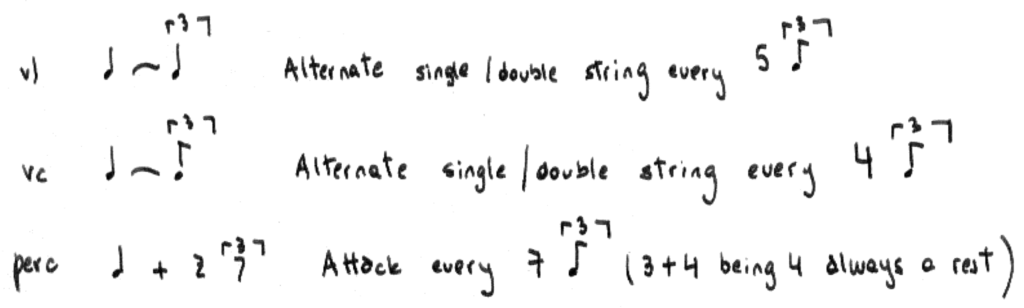

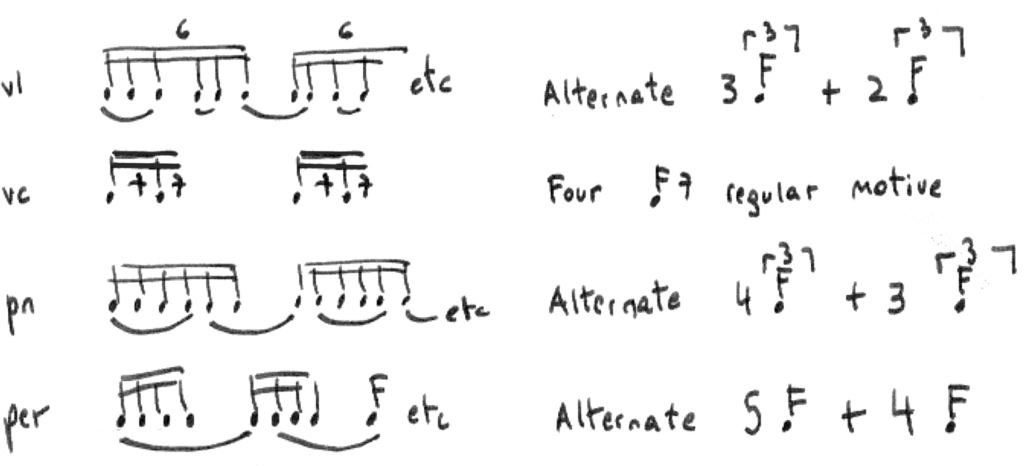

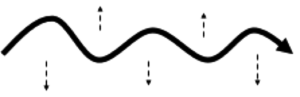

Micro-isorritmos: expansión y contracción del tiempo

Encada sección (1, 2 o 3) cada instrumento repite exactamente la misma frase rítmica 7 u 8 veces, (depende del instrumento). La frase en bloque se expande o se contrae rítmicamente.

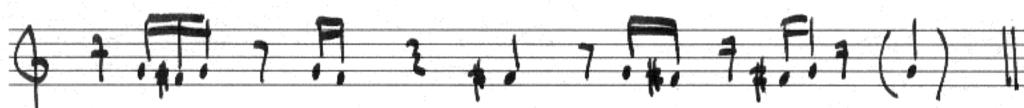

violoncelo compases 10-15. La misma frase se repite dos veces. La primera vez (compases 10 y 11) la unidad de tiempo corresponde a la corchea de tresillo, la segunda, a la corchea (el tiempo se expande).

Cada instrumento expande y contrae temporalmente su isorritmo. Esta estructura rítmica básica se va transformando cada vez en algo distinto por los cambios efectuados en los otros parámetros (cambian las alturas, la orquestación, los gestos, etc), pero las duraciones no se alteran.

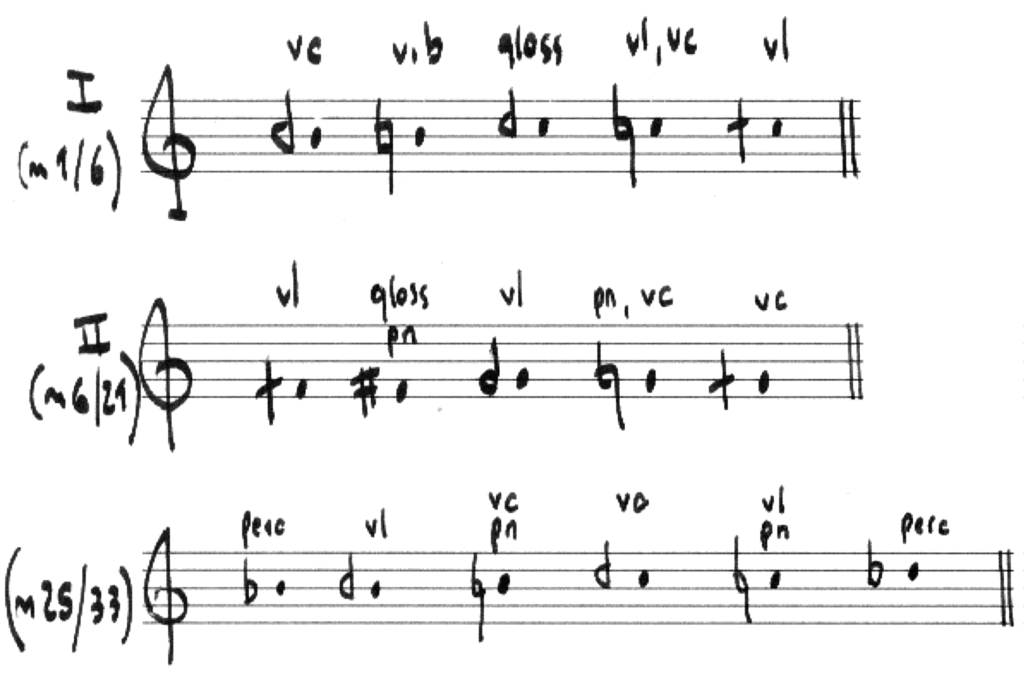

Expansión /contracción del pulso en el cello:

- corchea de tresillo (c. 10-11)

- corchea (c. 12-15)

- negra de tresillo (15- 19)

- negra de tresillo + semicorchea de tresillo (19-24)

- negra con punto (c. 25-33)

- negra ( 34-40)

- negra de tresillo (41-49)

Esta serie de secciones sucesivas en expansión y contracción están notadas en una grilla de cuatro cuartos. El compás es solo una grilla convencional y no representa ningún tipo de acento.

Recuerdos

En la sección 2 de la pieza hay motivos musicales que pertenecen a la sección anterior y que están “cortados y pegados” en forma idéntica y en el mismo lugar en relación a la sección 1. Son citas textuales del pasado de la pieza, o juegos de la memoria. Cada instrumento tiene una recurrencia y debe ser tocado exactamente de la misma manera que en la sección anterior. Pero los recuerdos o rememoraciones son individuales, por lo que el contexto de estas memorias es ahora diferente en relación a los demás instrumentos.

violín: 88-98 cita de 39-49

cello: 74-82 cita de 25-33

percusión: 68-71 cita de 19-22 (¡esta es la razón que vuelve a tocar con baquetas!)

piano: 80-82 cita de 31-33

Horizontal versus vertical

Parafraseando la polifonía medieval., lo importante es que cada línea horizontal es bastante autónoma, teniendo a la vez algunos puntos de encuentro con las otras voces.[2]

La dialéctica de esta pieza se basa en las cuatro voces individuales que se expanden y contraen y en los puntos de encuentro que cada uno tiene con las otras voces.

Estos puntos de encuentro están “congelados” y funcionan como una estructura superpuesta (impuesta) sobre la dinámica de movimiento de las voces individuales. Están marcados en la partitura con flechas verticales.

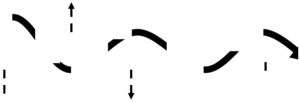

Estos puntos de encuentro tienen un rasgo diferente en cada una de las tres secciones:

Sección 1: un mismo acorde mi3-fa3 (y sol 4)[3], con distintas disposiciones y colores instrumentales, pero siempre con las mismas alturas. La idea es que es el mismo objeto bajo diferentes perspectivas.

Sección 2: respiración (inhalar o exhalar) compartida.

Sección 3: acorde con la letra [m], bocca chiusa. La altura de este acorde es siempre variable, el timbre homogéneo.

Los puntos de encuentro deben ser siempre precisos en el ataque.

La pieza es una deriva horizontal “atada” con nudos verticales.

La alquimia de los materiales

La expansión y contracción rítmica de la pieza sirve como una estructura elástica que “soporta” diferentes materiales a lo largo de la pieza.

Sección 1: scordaturas extremas, siempre en armonía de cluster. La altura progresivamente va desplazando en bloques de la zona de G2 a la zona de C3, ida y vuelta en algunos casos.

El acorde “nudo”, mi-fa (sol), que nunca se traspone.

Sección 2: frotados y sonido de aire

Sección 3: textos, uso de la voz y luces.

Cada sección se va “transformando” en la siguiente de forma mas o menos progresiva.

Si bien cada una de las tres secciones es clara y distintas, el paso de una a otra no debe ser brusco.

La obra detrás de la obra

Puedo hablar acerca de mis intensiones al escribir la obra, pero sabemos que las intenciones de los compositores y el resultado musical son a menudo mundos bastante disimiles. Me gusta mucho hablar de mis ideas musicales un poco como si fuera literatura, o ficción, pero gusta mucho mas ver las distintas interpretaciones que los músicos tienen sobre mi trabajo.

La historia de esta pieza es el intento de escribir una música que se va desprendiendo de sus rituales.

La obra comienza en el “borde” de los instrumentos. Es la zona donde los instrumentos pierden su familiaridad, pero todavía son reconocibles. Son “instrumentos’, pero en un limite de imposibilidad: extrema scordatura, piano preparado, percusión que se expande a las partes menos resonantes de los instrumentos.

En la segunda sección, los instrumentos son mas “periféricos”. De las partes resonantes nos desplazamos al cuerpo de los instrumentos, de las baquetas a las manos.

En la tercera sección, los instrumentos son abandonados. La voz, las luces del atril, algunos objetos encontrados como el papel de embalaje abandonan todo gesto tradicional. Los instrumentos son contendedores, cajas de resonancia de otros sonidos externos.

Es posible recrear un escenario diferente al final de la pieza: el pianista esta debajo del piano, el cellista para producir las resonancias dentro del instrumento puede también recostarse sobre el piso al lado de su instrumento, o recostar solo el instrumento o buscar cualquier otra posición escénica que no remita a la posición tradicional de tocar el cello. Lo mismo para la percusión y para el violín, que pueden buscar otras posiciones en el escenario diferentes a las habituales (dar la espalda, pararse, sentarse en el piso, etc). Lo que es importante es elegir el momento de hacer los cambios, que deben ser graduales y nunca forzados. Tal vez es bueno tocar sin zapatos para no hacer ruido al desplazarse y con ropa cómoda, para evitar crear situaciones extrañas o que generen una expectativa extra.

A rasgos generales la pieza comienza con una situación de concierto standard, y termina con gente “desparramada” en el living de una casa.

Es una sugerencia. La obra también puede ser tocada en forma casi convencional del comienzo al fin.

Las luces:

Cada instrumento hace su aparición con la luz de atril que se prende, una a una, como un ritual decadente de una situación de concierto que se va a fracturar.

La pieza se empieza a desprender de los músicos en un momento, las luces se convierten en un material, que existía desde antes, pero que ahora tiene un significado musical diferente (el “afuera” de la pieza se vuelve “adentro”).

También las luces funcionan como la expresión de mostrar un ritual ya vacío de contenido: la luz del piano se prende y se apaga, pero el pianista NO esta en el banquillo. La luz alumbra una partitura que nadie lee. Lo mismo se puede hacer con los otros instrumentos (no necesariamente con todos, con el piano es suficiente, tal vez seria lindo agregar también el cello).

Finalmente, la obra termina en la oscuridad. La función de la luz de atril se desprende de la función de la música, que sigue sonando sola. La salida sincronizada de las cuatro voces que apagan los interruptores sucesivamente, uno a uno, sigue poniendo la pieza en un marco de pensamiento organizado.

Habría que determinar el rol del director en este contexto. Una opción es que el director siempre dirija mas allá de que la pieza se desbande, al final termina dirigiendo un ensamble que no lo ve. Otra opción es que el también acompaña el proceso de desmaterialización, y sigue cumpliendo su rol de una manera anti funcional (ej., dirigir de espaldas o cualquier otra cosa).

Seria lindo que ustedes formulen su propia propuesta del comienzo al final en caso de que quieran profundizar en una puesta escénica. Estas son solo algunas sugerencias.

Cuestiones prácticas:

Esta es una idea base que cada ensamble debe adaptar y reinterpretar de acuerdo a sus ideas y posibilidades musicales y técnicas.

Es mejor aprender algunas secciones de la pieza de memoria, para tener mas independencia de la partitura (sobre todo en las posiciones no convencionales de los instrumentistas: abajo del piano, sentados en el piso, etc). Otra opción es tener una segunda partitura en la nueva locación, o un ayuda memoria.

El tema de los interruptores, creo que se puede trabajar de la siguiente manera.

1) Luces de atril normal, pero con un interruptor de pie para el cello y el piano. Si ambos están en el suelo, o fuera de su silla, todavía pueden alcanzar el interruptor.

Hay que establecer un código de entradas para las secciones donde los instrumentistas tienen ataques conjuntos y no tienen contacto visual entre si y tal vez tampoco con el director. Es un problema a resolver.

[1] Filtrado significa “borrado por zonas”. Es un filtrado por bloques donde simplemente se escinden algunas secciones. Las secciones que quedan son exactamente iguales al original, no están transformadas.

[2] Al momento de armado de la pieza, es importante que cada instrumentista se concentre en su línea. Cada frase debe sonar mas lenta o mas rápida que la anterior siempre en relación si mismo, estableciendo puntos de encuentro con las otras voces. En el ejemplo anterior, si el cello entra tarde en el compás 12 es un “mal menor”. Lo importante es que los dos motivos rítmicos de su línea, primero en tresillos y luego en corcheas conserven una relación exacta (uno es mas rápido que el otro, pero ambos son la misma cosa a distintas velocidades). Acortar el silencio interno de un motivo es desfigurar el motivo y eso es un mal mayor. Si la sincronía con el violin esta desfasada, no importa tanto como que el motivo rítmico se desfigure.

[3] el sol 4 aparece esporádicamente